I’ve recently finished reading Ernest Hemingway’s Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast, written in the 1920’s while he worked for the Toronto Star as a foreign correspondent. The novel chronicles his personal accounts and experiences living in the city and his observations about life and the people around him. It’s a rather priceless and rare look inside his life as a struggling young writer and his first hand accounts of interactions with such famous writers as Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and of course, Gertrude Stein. The title of the book originated from a conversation Hemingway had with his biographer. He commented that Paris leaves an impression on those who live there. Anyone who has lived there as a young person can attest to the fact that the city will stay with them for the rest of their lives. In essence: Paris is “a moveable feast”.

A Moveable Feast was published posthumously in 1964, three years after Hemingway’s death. Edited by his fourth wife Mary, it was compiled using the unfinished manuscript and a collection of material which Hemingway had indicated he did not want included in a final draft. At the time of his death he had not wanted his Paris memoirs published because he felt it lacked a true ending and was therefore not a complete story. A restored edition was published in 2009 by Hemingway’s grandson Sean. This was intended to more accurately reflect the original work of Hemingway, disregarding the majority of Mary’s edits. It’s widely agreed that the new version can’t be regarded as any more definitive than the original. Ann Douglas, professor of literature at Columbia University put it best when she said “there can be no final text because there is not one.”

One of the things I loved most about A Moveable Feast was the simple pleasure of being able to read about Hemingway’s life in Paris as a young man. His vivid descriptions of the city transported me to the Boulevard St-Germain & Place St-Michel. His incredible eye for detail was able to capture what makes Paris a timeless city. He is able to describe the simple staples of Parisian life with intimate articulation. Hemingway encapsulates the most wonderful and rewarding experiences: be it strolling across the Luxembourg gardens, wandering through the Latin quarter, or sitting in cafes enjoying a café crème while observing people.

A common theme throughout A Moveable Feast is the poverty in which Hemingway and his first wife lived. Many times Hemingway makes reference to their poor financial situation. He writes about life in the city’s poorest neighbourhoods and the sacrifices they made on a daily basis to get by. He paints a portrait of his early life and the struggles he experienced as a writer while having to endure continuous hardships. Despite their circumstances, I was most shocked by their ability to live such a full life. Hemingway writes:

“But then we did not think ever of ourselves as poor. We did not accept it. We thought we were superior people and other people that we looked down on and rightly mistrusted were rich. It had never seemed strange to me to wear sweatshirts for underwear to keep warm. It only seemed odd to the rich. We ate well and cheaply and drank well and cheaply and slept well and warm together and loved each other.”

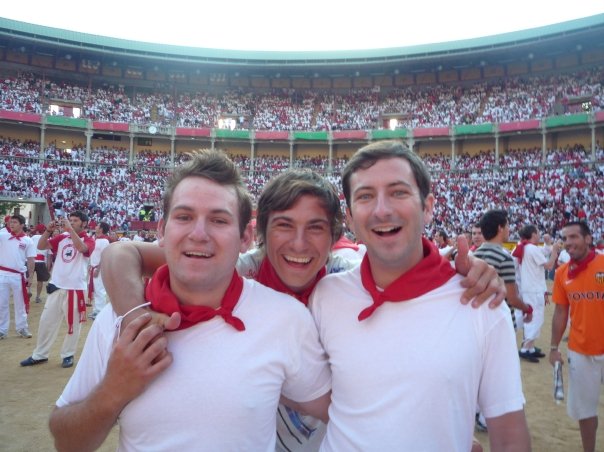

They made sacrifices to have the life they wanted: a life full of rewarding activities with those close to them. If affording this life meant having to use public baths by the river, or having to often skip lunch, or borrowing books instead of purchasing them from Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company, it was all in an effort to be able to enjoy a lifestyle that made them happy. Spending the money they saved on dining out with friends and on European excursions, such as winter in the mountains for a skiing holiday or summer in Spain for the San Fermin festival, shared a common theme.

Hemingway chose to spend his money on experiences and in no way was he the last person to promote such a lifestyle. David Chilton, author of The Wealthy Barber, suggests that people shouldn’t be afraid to admit when they can’t afford something and encourages spending more money on experiences rather than on “stuff”. Hemingway was able to live well while poor, not because it was easier back then, but because he understood what was important. Being able to live a life surrounded with good friends, good food, and good drink was the foundation not only to a fulfilling life for him but also a starting point for many of his great stories.

In the original version, the book is concluded with a rather fitting last line: “But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy.” This still holds true almost a hundred years later. Just below the pricey restaurants and cafes is a vast expanse of places where people can go and still enjoy a great quality of life on a budget.